Getting a bus from Chengdu for some of the way was the only way to cover the over 2000km to the Laos border with more than 3,500 metres ascent in the 28 days left on my visa. The town of Litang is located at an altitude of 4,014 metres (13,169 ft) among open grasslands and surrounded by snow-capped mountains. Its actual altitude is about 400 metres higher than Lhasa, making it one of the highest towns in the world.The thought of getting there by bus from Chengdu at only 500 metres of altitude was most attractive!

After three weeks off the bike in Chengdu and Hong Kong I knew I had lost all the acclimatisation I had gained during weeks and weeks of cycling above 3000 metres and with some mountain passes of over 4,600 metres ahead of me, I was glad there was no direct bus to Litang and I had to break the journey and stop at a town called Kangding (2,900 metres) where I could begin to re-acclimatise.

Something I have loved about China is the daily dancing in the square in the evening. Everyone, young and old take part. In Kangding they was dancing in two squares and I had the chance to put to good use my ballroom dancing skills by asking local women to waltz with me much to the amusement of the locals.

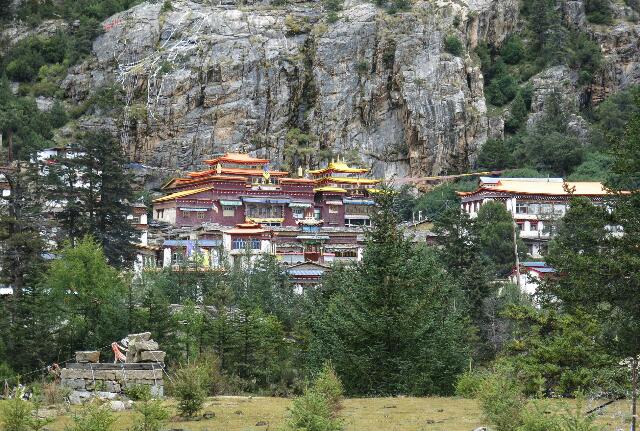

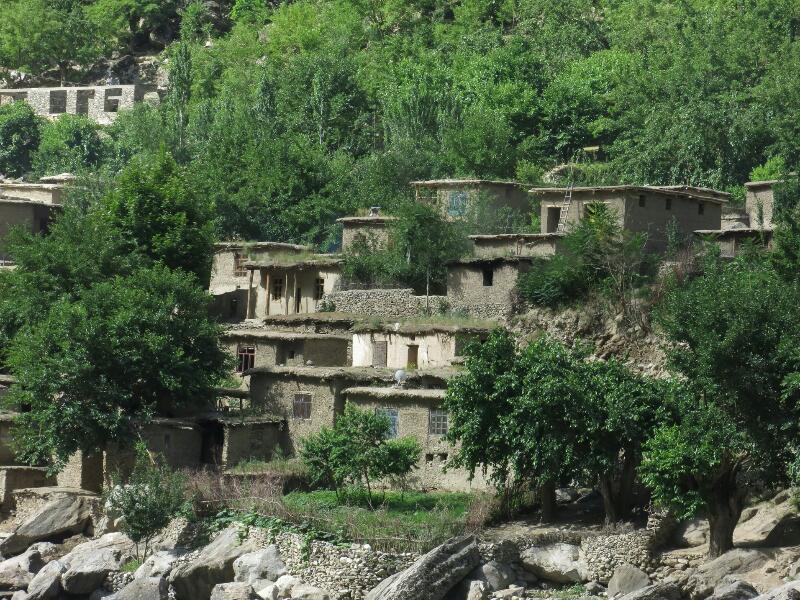

On the way to Litang the bus climbed and climbed going through Tibetan villages with their fortress like houses, once again the yaks made their appearance, older people with weathered faces sat by the road constantly spinning their hand held prayer wheels and women combed their long hair outside their homes, thin plumes of smoke coming out of their chimneys. I was back in the Tibetan world.

Litang felt like a place in the middle of nowhere. This sleepy town was the birth place of the 7th and the 10th Dalai Lamas and very much at the centre of Tibetan resistance to the imposition of the communist rule in the region and as a consequence was heavily bombed but life now had no obvious reminders of those days.

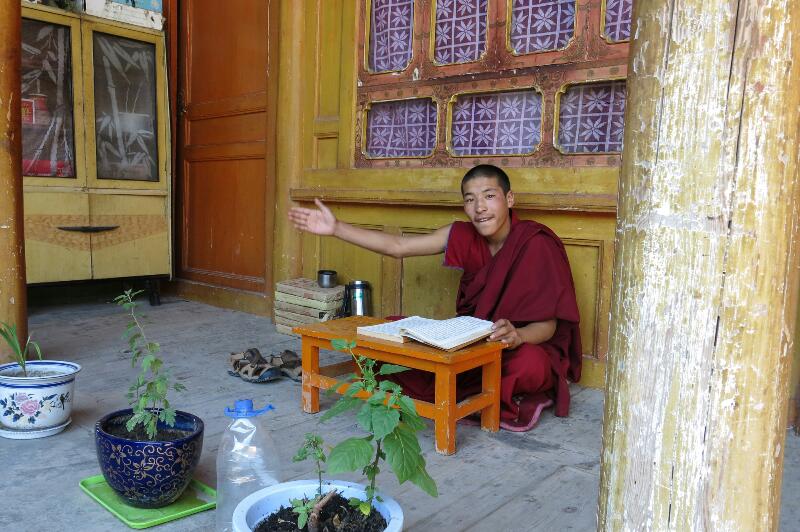

One of the rituals that was forbidden from the times of the Cultural Revolution of 1960s until the 80s was the Sky Burial practice. Visiting one of the local sky burial sites was my lasting memory of Litang. It was nearly dusk when I went there with three French cyclists lodging in the same hostel as me. We threaded our way through the narrow streets of the village to an area in the mountainside covered in prayer flags, our breathing laboured due to the altitude. Rubble, discarded plastic bottles, old shoes and other rubbish scattered around; I could feel myself reacting to these surroundings, surely this environment wasn’t respectful of the dead. We reached the prayer flags but could see no evidence of sky burials. It was getting darker and the lights in the village below were coming on as we headed to a pile of stones on a slope to the side of the flags. To start with we came across a knife here and a feather there and then we saw big piles of discarded knives, scissors, axes, rocks marked by sharp instruments and a big block of wood whose scars made clear what it had been used for. Hundred of small fragments of human bones and feathers were scattered in bold spots in the grass. I shuddered, imagining the macabre feast that took place in those spots and then I remembered the words of the Zoroastrian couple I stayed with in Yazd (Iran): “Sky burials are a beautiful act of generosity, giving the human body back to nature”. I realised that for the second time in less than one hour the deeply engrained Catholic belief system of my upbringing had got on the way and I made a conscious effort to look at the place and the whole ritual with different eyes but I just couldn’t. It was time to get back to the hostel.

Over the next few days I stayed above 4000 metres plodding up to high passes. On a particular day I was delighted to have crossed a pass that was nearly 4700 metres high without much difficulty, I was tackling the second one of the day when the headwind started and I realised how close I was to the limit of my physical capability, I couldn’t stay on the bike any longer and I had to push my way through the second pass. I still had more than 10 kilometres of ondulations between 4600 and 4700 metres to the nearest village and I couldn’t go on, I had to stop and camp but where? All there was around me where big boulders and lakes. Eventually I saw a tiny piece of grass by the side of the road and pitched my tent and crawled into my sleeping bag. It rained non stop all night, in the tent it was like being inside a drum and in spite of being exhausted I found it difficult to sleep.

The following day I got up ready to climb the highest pass of the trip, 4716 metres. Soon it became clear I would never reach the nominal targets had given myself. It was then that sitting by the side of the road I met Pablo from Zaragoza in Spain How nice to meet someone with shared language and culture! We sat together for a while sharing stories and soon enough we decided to hitch a lift to the pass and if not successful camp as soon as possible. After a couple of failed attempts a tractor stopped and took us both and our bikes 10 kilometres up the hill towards the pass. Switchback after switchback the tractor climbed impossible gradients. It would have taken me hours and hours of pushing and half heartedly cycling to have covered that distance. It was the most wonderful of feelings to be standing on the muddy tractor’s cart, breathing its petrol fumes, seeing the cooling water spluttering out of its noisy engine whilst holding onto the bikes for dear life and seeing the village at the bottom of the valley getting smaller and smaller in the mellow light of the evening. I was exhiliariated, thrilled, happy. The moment was just perfect, I didn’t need absolutely anything else.

At the pass it started raining but as we got lower down it stopped. We followed the most beautiful valley and found a good camping spot. Scrambled eggs with Chinese sausage, a beer and great conversation finished off an excellent day on the road. As I was going to sleep I made the decision to take a bus to Shangri-la and miss out on the last really big climb in China. Rationally I knew it was the right decision but I couldn’t help feeling a pang of disappointment at having to make it.

From Shangri-la I cycled to Tiger Leaping Gorge which was as spectacular as its name promised. The gorge it’s one of the deepest and most spectacular canyons in the world. It gets its name from a legend that tells how a Tiger jumped from one side of the gorge to the other to scale from hunters. I had come down a steep hill when the gorge came upon me all of a sudden and it took my breath away. To see the Yagtse, the longest river in Asia and the third longest in the world, the mother River as the Chinese call it, squeezed into such a channel only 25 metres at its narrowest point was awe inspiring.

I was at a much lower altitude now and able to cope with the ondulating terrain enjoying some beautiful old towns and wondering around their markets.

Feeling more energetic, I now could cover longer distances on the bike fuelled by the food from small stalls which looked pretty dirty but as the food came from huge cauldrons of boiling stock I wasn’t too concerned about the state of the places.

As the daily distances got longer I found myself entering a meditative space – thinking a lot and at the same time not thinking at all. I revisited moments and situations if my life from the safety of time and geographical distance, occasionally getting ‘light bulb’ moments that helped me understand myself a bit better. I remember one day when I was sitting in the courtyard of an old Chinese house in a town called Dali, a quiet, peace space with pots of azaleas and fuschias around a gold fish pond. In my mind I went to my London garden and I saw myself planting ivy underneath its huge fatsia shrub, adding clumps of colour with big pots of bulbs and annuals. I realised that the love of and for my daughters, for my family and friends; the knowledge that my house and garden are waiting for me give me the deep roots I need to feel safe enough to be a nomad for a while.

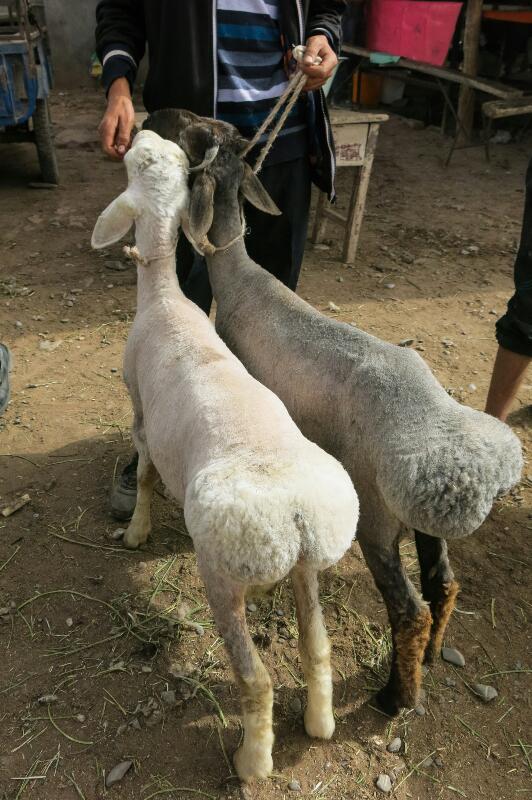

As a nomad it is my second harvest time. I was in Romania this time last year, thousands of kilometres away, in China, I’m witnessing the same frantic activity: peasants harvesting the crops, ploughing and feeding the fields, lighting fires to burn the scrub, bent over by the weight of the huge bags of grain they are carrying on their backs. Scenes that have been repeating them unchanged for centuries.

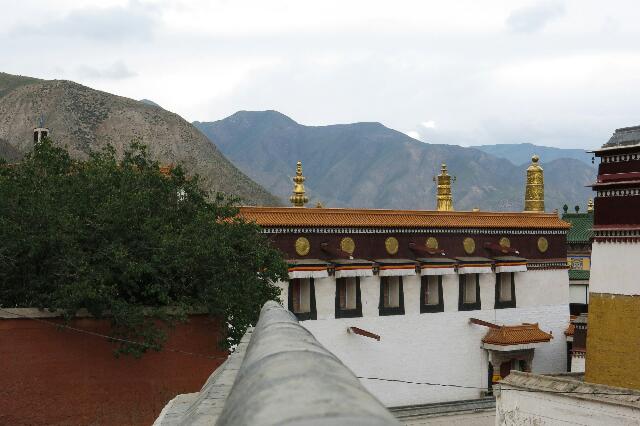

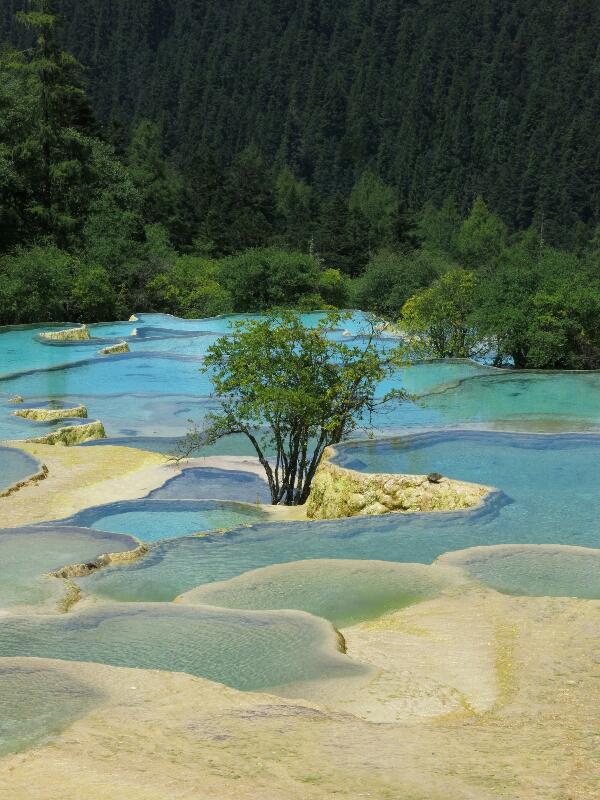

The time for my visa was get tight so I caught my very last Chinese was to bring me 300 kilometres from the Laos border to a town called Jinghong. Once again a new world opened up, this one full of tropical vegetation, golden peacocks decorating the roofs, Buddhist temples and statues of elephants and gorgeous Botanical gardens but then each part of China has been very different – the Kasbah like old town of Kashgar, the mud Amdo Tibetan villages, the tents of the nomads in the grasslands, the ochre and yellow Muslim houses of Gansu, the fortress like towers and curvy tiled roofs of Si han, the wooden houses in the rice fields near Guilin, the castle like Kham Tibetan houses, the stone courtyards in Dali and Lijiang and now the golden peacocks of Xixuangbanna. Like everywhere I’ve been, this is not a homogeneous country, houses, people, food it all points to difference. It is these difference that is making my trip so fascinating and yet it is what we have in common as human beings that is making it possible, the ability to connect with the hundreds of people I’ve met in the 2,340 kilometres I’ve cycled in this country.

I was leaving Jinghong and had stopped at a bike shop to fix the mudguards of my bike damaged in my last bus journey. I asked directions to my next destination from the shop owner and totally blasse he answered: “Follow the Mekong” so off I went to find the mighty river. For quite a few kilometres, silently and with excitement, I repeated the instructions in my head: “Follow the Mekong”, “Follow the Mekong” what incredible directions I’ve been given, I thought, for him they may be quite ordinary, the same as for someone in London to say “get on the M25” but they conjured up all sort of exotic images in my mind.

Laos is somewhere near following the Mekong…

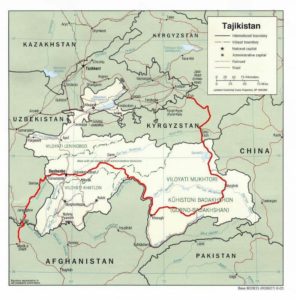

In its full length, the Highway goes from Osh, Kyrgyzstan and traverses the whole of Tajikistan to end in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. I cycled it from Dushanbe to Osh via the Northern route to Kala-i-Khumb and the Wakham Valley.

In its full length, the Highway goes from Osh, Kyrgyzstan and traverses the whole of Tajikistan to end in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. I cycled it from Dushanbe to Osh via the Northern route to Kala-i-Khumb and the Wakham Valley.

In Armenia I pushed my bike uphill more than in the previous 9 months put together. Gradients of 12% are common and the road surfaces appalling. It was just impossible to cycle up those hills even in my granny gear but the scenery was worth the effort. Enormous canyons, huge snowy mountains, mirror like lakes, monasteries perching in the top of cliffs, villages hanging for dear life in the slopes.

In Armenia I pushed my bike uphill more than in the previous 9 months put together. Gradients of 12% are common and the road surfaces appalling. It was just impossible to cycle up those hills even in my granny gear but the scenery was worth the effort. Enormous canyons, huge snowy mountains, mirror like lakes, monasteries perching in the top of cliffs, villages hanging for dear life in the slopes.

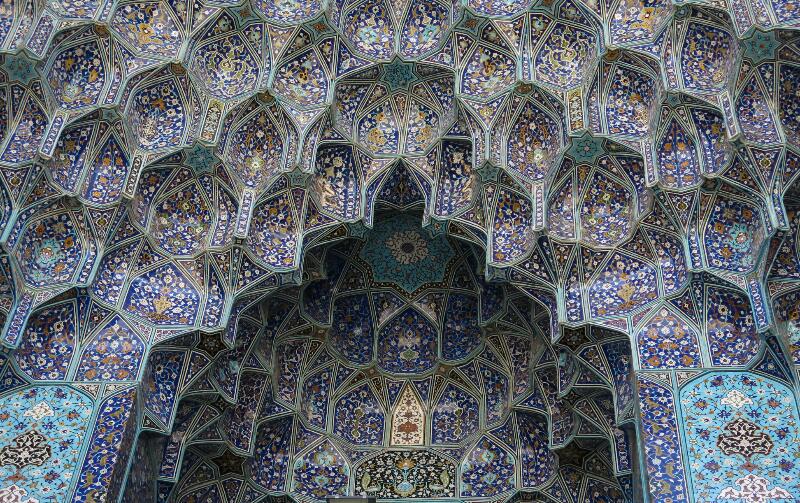

I continued pushing my bike up impossible gradients, crossing high mountain passes, sleeping in beautiful woodlands until I got to the border with Iran when all of a sudden the mountains where changed by a deserts. I had arrived in Iran.

I continued pushing my bike up impossible gradients, crossing high mountain passes, sleeping in beautiful woodlands until I got to the border with Iran when all of a sudden the mountains where changed by a deserts. I had arrived in Iran.